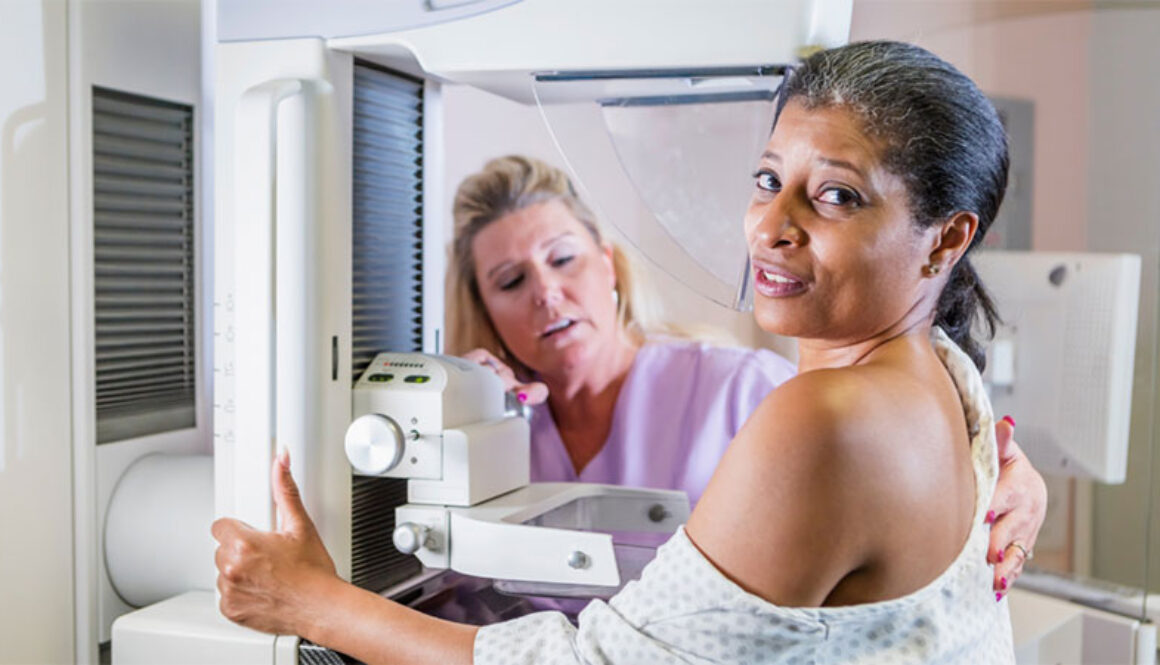

For the last 50 years, mammography has been used for breast cancer screening. As a gynecologist for over 25 years, I’ve encouraged thousands of women to get their mammograms done on a regular basis.

Many of my patients confided in me of their dread of the procedure. Their issues were the pain of breast compression, the concern for radiation exposure, the anxiety of frequent call-backs requiring additional images and/or biopsy, and the fact that the study has severe limitations in accuracy for women who had dense breasts. Despite their pleas for something different, I would encourage them to get screening, because I really believed it was in their best interest. Didn’t they want to catch breast cancer at the earliest possible stage?

Over time though, I started to have my doubts. As a doctor, I took an oath to “first do no harm.” I began to wonder if recommending mammograms and my Hippocratic Oath could possibly be in conflict. I dealt with these concerns by having an honest conversation with my patients about the risks and benefits of mammography. At the conclusion of these conversations, I would offer my support for them, whatever THEIR decision was.

Now that I’ve learned more about true wellness, the causes of illness and studied the statistics of mammography in depth, I am compelled to have an honest conversation with whomever will listen. Women deserve to know this…

What exactly IS a mammogram and how does it detect cancer?

A traditional screening mammogram is an x-ray study of the breasts in two orientations–top to bottom, and side to side (the medical terms are craniocaudal and mediolateral, respectively). This provides a 2-dimensional view. The goal is to detect abnormal calcification clusters that are present in many breast cancers.1 The hope is that detecting these calcifications before a lump is felt will lead to earlier diagnosis of cancer, making treatment easier. The ultimate goal is to decrease death from breast cancer.

In 2011 a new version of mammography was introduced, that allowed an approximation of a 3-D image, by stacking the 2-dimensional images on top of each other. This is digital tomosynthesis and involves the same initial set up of the patient, stabilizing the breast in two orientations. The images are obtained by having the x-ray camera rotate around the breast during the study, taking multiple pictures over a period of about 7 seconds.2

With either traditional mammography or the newer digital tomosynthesis, to get a decent view, the breast must be compressed between two plates to thin out the tissue. Otherwise, it’s impossible to see clearly. For women with large breasts, more than two images per breast are often required to include all the breast tissue. If the interpreting radiologist sees something he/she’s not sure of, then additional views with mammography, ultrasound, MRI and/or biopsy is recommended.

What are the limitations of mammography?

There are several limitations to mammography…

Missed cancers (false negatives)

Not all breast cancers have calcifications, and these are missed with mammography. For instance, lobular cancer is usually not detected on mammogram, and this makes up about 10% of breast cancers.3

Dense breast limitation

For women with dense breasts, meaning a higher ratio of fibrous to fat tissue, the mammogram is difficult to interpret. The dense breast looks brighter on x-ray, and small calcifications are easily obscured. This is a significant limitation, because over 40% of women have dense breasts.4 In these women, it is estimated that a mammogram could miss up to 50% of cancers.5

False positives

Half of women screened over a 10-year period will have a false positive mammogram. This occurs when the call-back for additional views and possible procedures ends up being non-cancerous. While around 12% of 2-D screening mammograms are recalled for more work-up, only 4.4% of those recalls, or 0.5% overall, conclude with a cancer diagnosis.6

Now, I’m truly glad that the woman involved doesn’t have cancer, but what about all the money, time, anxiety, and risk of complications from procedures that she spent to get the clean bill of health? Recently, a woman in my practice had her recommended mammogram and a call-back for additional views that culminated in a biopsy. The good news is she didn’t have cancer—the biopsy was benign. The bad news is that she developed a large painful hematoma from the biopsy and has been dealing with that for a long time.

Are there risks to mammography?

With anything in medicine (and all of life, really) there are risks and benefits. The same is true with mammography. The term “risk” implies potential harm caused by the procedure. There are both quantifiable risks (meaning we have data and can calculate the percentiles) and subjective risks.

The quantifiable risks of mammography

Radiation

Radiation exposure is inevitable by the nature of mammography. Women with large or dense breasts typically require higher dose radiation per study than women with small, non-dense breasts. Overall, the radiation exposure is not much per individual study, but we think the risks of radiation exposure are cumulative, which mean they add up over time.7 Could this cumulative exposure become significant when we start regularly radiating the breast at age 35-40 and continue until a woman is in her 70s?

Breast trauma from compression

Mammographic compression involves forces of up to 45 pounds on the breast. This is needed to layer the tissue thin enough to detect lesions. There have been numerous reports of beast hematomas following mammogram, sometimes requiring surgical intervention to drain.8

Do the above two risks translate into mammography actually being a risk for CAUSING breast cancer?

The answer is definitely yes, for radiation exposure, but not proven for trauma. Multiple case reports of cancer after trauma have been discussed, and prior to the invention of mammography, multiple texts listed breast trauma as a risk factor for cancer.9-11 Now though, experts are adamant that the trauma from compression does NOT cause cancer.12

Multiple sources have quantified the risk of mammography-induced cancers from the lifetime radiation exposure of the procedure. A study out of Japan calculated that for every 100K women screened annually (receiving 3.7 mGy each study) from 40-55 years, biennially from 55-74 years, there are 86 radiation-induced cancers and 11 deaths.13

The above data was extrapolated from atomic bomb survivors, which was exposure to high energy gamma radiation. Mammograms deliver lower frequency radiation, but that might actually be worse. A study out of England reported that low energy X-rays used in mammography are approximately four to six times more effective in causing mutational damage than higher energy gamma rays. Since current radiation-risk estimates are based on the effects of high energy gamma radiation, this implies that the risks of radiation-induced breast cancers from mammography X-rays are underestimated by the same factor.14

Yikes! That means that there could be 516 cancers (86 x 6 = 516) caused by mammographic radiation and 66 deaths from these cancers. I’m not a math major or statistician, but that sounds like a lot to me.

Despite these well-thought projections, The National Breast Cancer Foundation adamantly proclaims that the amount of radiation used in a screening mammogram does not cause cancer.11

Overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis is my BIGGEST concern. It’s a complicated issue, but I’ll try to help you understand it… The ultimate goal of mammography is to prevent death from cancer by early detection. The concept of overdiagnosis is that there are small cancers that would never cause death. This is because they are so slow growing, or because the immune system can sometimes step in and solve the problem with no outside interventions. Treating these cancers does nothing to prolong your life. In fact, treatment has multiple risks such as:

- Complications from surgery

- Radiation treatment has long-term potential complications such as an increased risk of heart disease15

Overdiagnosis is a situation where the cancer would never have been detected without the screening, and would never have caused symptoms, so the woman would have lived her life without ever knowing or worrying about cancer, and would have lived as long as she was going to live, dying from some other cause.

The problem is that once you see cancer, it’s almost impossible NOT to recommend treatment. Because at diagnosis, we have a snapshot in time. We don’t know what the true long-term behavior of a tumor will be unless we watch it, and nobody really wants to watch a cancer, in case it’s a more aggressive kind that would have a bad outcome. The usual reaction to cancer is “Get it out of me!”, understandably so, but there are likely many cases where that’s not increasing life expectancy, and may even be decreasing life expectancy, due to the complications of treatment from overdiagnosis.

These concerns were eloquently discussed in a report out of Norway where the authors concluded: “For every 2000 women invited for screening throughout 10 years, 1 will have her life prolonged. In addition, 10 healthy women, who would not have been diagnosed if there had not been screening, will be diagnosed as breast cancer patients and will be treated unnecessarily.”16

Cost

While most insurance companies cover the screening mammogram, many do not cover the additional studies. Even the accompanying ultrasound that is recommended for women with dense breasts (to make up for the painfully inadequate mammogram) is not always covered. These costs can be substantial, ranging from $700 to over $5000, depending on the amount of work-up required. The breast cancer screening industry is an $8 billion industry in the United States.

The subjective risk of mammography

Anxiety/Stress

The subjective risk pertains mainly to the limitations of mammogram studies that lead to callbacks for additional studies.

The anxiety induced by the call backs can be significant. There’s always a waiting period between when a woman is notified of questionable findings and when the most-likely “all-clear” from the additional studies is finally given. During this time, she is often worried about a cancer diagnosis.

Some women also have anxiety because of the pain they experience from the compression of their breasts necessary to obtain the mammogram. And if they’ve ever had bruising or a hematoma, it may be magnified.

The effects of stress on the body are significant and a well-known cause of long-term disease.

The benefits of mammography

As already mentioned, the goal of mammography is to detect cancer early, making treatment easier and hopefully resulting in a lower death rate from breast cancer. That is a very noble goal. How has it panned out?

Unfortunately, not as good as we had hoped. Here, we must be sure to acknowledge the difference between death from breast cancer, and overall mortality. Death from breast cancer is just like it sounds, whereas overall mortality is death from all possible causes, including breast cancer. I would argue that for the person who is dead, it probably doesn’t matter to THEM what their cause of death was…

Probably the most thorough study on this was the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. Here’s the most recent data from that study on the effectiveness of mammography screening:

The “intervention” group included those who underwent mammography. Note that the while there were 20 less breast cancer deaths (per 100,000) there were 89 ADDITIONAL all-cause deaths (per 100,000) in those who participated in mammography screening.17

Missing informed consent

Informed consent involves an honest conversation, laying out all that we know regarding an issue, and letting the patient weigh the pros and cons to make her own decision. This is the duty of medical professionals, yet it seems to be missing with mammography.

Women aren’t told about the risks of mammography. We are simply encouraged to get them. In fact, I would go so far as to say we are scolded for being foolish if we don’t keep up with the not-infrequently changing recommendations. The studies discussing mammography from the earlier days, used the term “women invited to participate in screening.” Now, instead of being invited to screen, we are admonished if we don’t screen.

I believe that we are intelligent beings and should be allowed to make informed decisions about our health. To do so we need to be given ALL the information about the pros and cons, the risks and benefits.

I don’t believe that the average physician has ulterior motives. I think they believe that the governing medical bodies have fully considered all these things and they are following the guidelines. I used to be one of those physicians.

But now that I know what I know, I can’t unlearn it. I’m concerned that mammograms are NOT as good as we thought, and may actually cause more harm than good. Women deserve to know ALL the facts and be championed for making their own decisions, not bullied into a screening program that has significant issues.